Here's How to Welcome Baby Birds to Your Yard

Register today to design your dream garden

Greetings, Yardeners!

I spoke yesterday about yardscaping for bird lovers at the Cedar Keys Audubon and I’m now going to share the “Why, How, Wow!” with you. But first, it’s time to start designing your dream garden by registering for our upcoming workshop.

Register now for Quick and Easy Yard Layouts

Anyone who thinks that gardening begins in the spring and ends in the fall is missing the best part of the whole year. For gardening begins in January, begins with the dream. — Josephine Nuese, The Country Garden

Content: We’ll guide you in visualizing and then sketching a layout for your yard with the key elements of a joyful landscape. You’ll leave with tools to test it on the ground so you’ll be ready for spring planting.

Where and when: On Zoom on Tuesday, February 11, 5:30 to 7 p.m. Eastern Time

Register: Become a paid subscriber ($30 per year) and we’ll automatically register you and send a Zoom confirmation. Or register for $25 plus service fees at Eventbrite.

Feedback from former students:

I'm so glad I signed up for this class. For the last couple of years, I've fantasized about 'getting my backyard together,' but I didn't know where to start. ... I'm so excited to achieve the plan that I've dreamt up for my yard in this class! — Martine, Washington, D.C.

Zoe and Heather are awesome teachers committed to their students' success. — Adam, New Jersey

Space is capped, so don’t wait to register!

The big “Why”

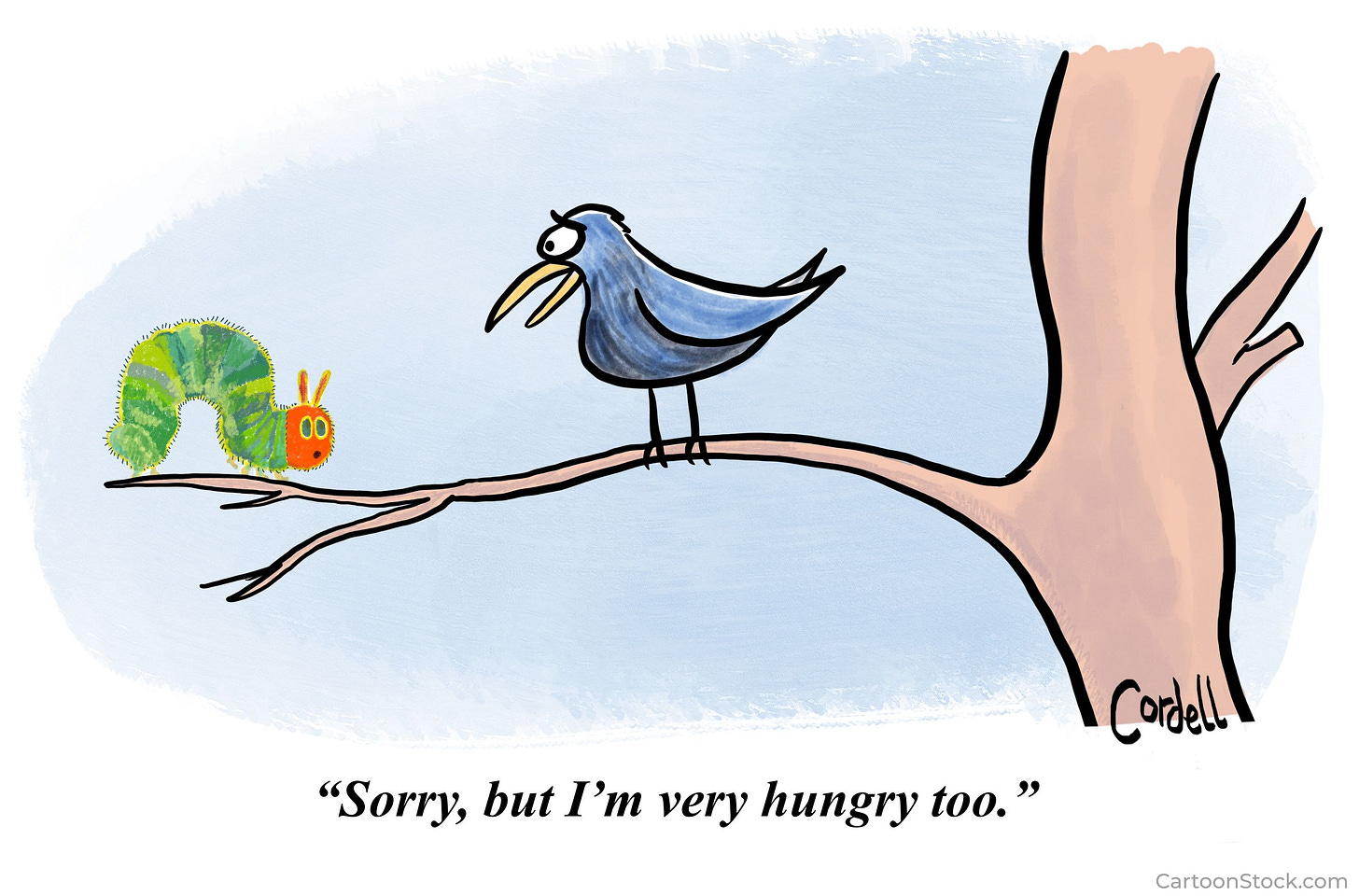

If we want to support breeding birds in our yards, then we need to support caterpillars. Research by entomologist Doug Tallamy and others has found that virtually all backyard birds feed their young insects, mostly caterpillars and adult moths. Caterpillars are high in protein, fats, and — most importantly — carotenoids, which birds can’t get from seeds and berries.

Most of North America’s terrestrial bird species, some 96 percent in fact, rear their young on insects rather than seeds and berries, and we are learning that in most of those species, the majority of those insects are caterpillars or adult moths. Caterpillars are so important to breeding birds that many species may not be able to breed at all in habitats that do not contain enough caterpillars. — Doug Tallamy, Nature’s Best Hope

The number of caterpillars needed to bring just one nest from birth to fledging is staggering: More than 6,000 caterpillars for one nest! Biologist Richard Brewer found that over the course of a typical 16-day nesting period, Carolina chickadee parents delivered 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars to bring one nest of tiny birds to fledging. And they continued to feed caterpillars to their young for another 21 days.

How

So, what’s a bird-lover to do?

1. First, do no harm.

That means don’t use pesticides — including “organic” or “vegan” pesticides. (See The Myth of Organic.) Entomologist Dan Kline told me that the barrier sprays used by pesticide companies, as opposed to municipalities, have a residual effect that kills beneficial insects as well as mosquitoes and other pests. And these pesticides may also endanger you and your pets.

2. Do less.

A lot of “neatening up” yard care is detrimental to caterpillars, as well as other beneficial insects, wildlife, and even vegetation. (See What to Do with Your Yard🍁Waste.) Most importantly for birds, you can create what Tallamy calls “pupation stations” for caterpillars by leaving leaves and logs under your trees instead of sending them to compost or landfill. According to Tallamy,

More than 90 percent of the caterpillars that develop on plants do not pupate on their host plants. Instead, they drop to the ground and pupate within the duff on the ground or within chambers they form underground. … Many caterpillar species bore into and pupate in decaying wood, a resource not available in most yards. … Finally, treasure your leaf litter. Many leaves that fall each autumn harbor small caterpillars within curled leaf margins, and dozens of caterpillar species eat fallen leaves. Replace store bought mulch with natural leaf litter whenever you can. —Nature’s Best Hope

3. Plant natives.

Species depend on the species they evolved alongside, so native plants host native caterpillars, which support native birds. While any amount of natives will support caterpillars, research on chickadees by scientists from the University of Delaware and the Smithsonian found the birds bred only in yards where more than 70 percent of the vegetation was native.

If the yard has more than 70 percent native plants biomass, chickadees have a chance to reproduce and sustain their local population. As soon as the number of native drops under 70 percent, that probability of sustaining the species plummets to zero. — University of Delaware

You can have all the birdseed in the world, but without native plants and caterpillar-friendly landscaping, birds will not be able to breed in your yard. Zoe and I always ensure that at least two-thirds of the plant species in our yards are native to our region, providing vital nourishment for birds.

Two-thirds for the birds

Zoe and I want to hear about your journey to a wild and wonderful yard. Please respond to this poll — and see the results in real time.

What’s native anyway

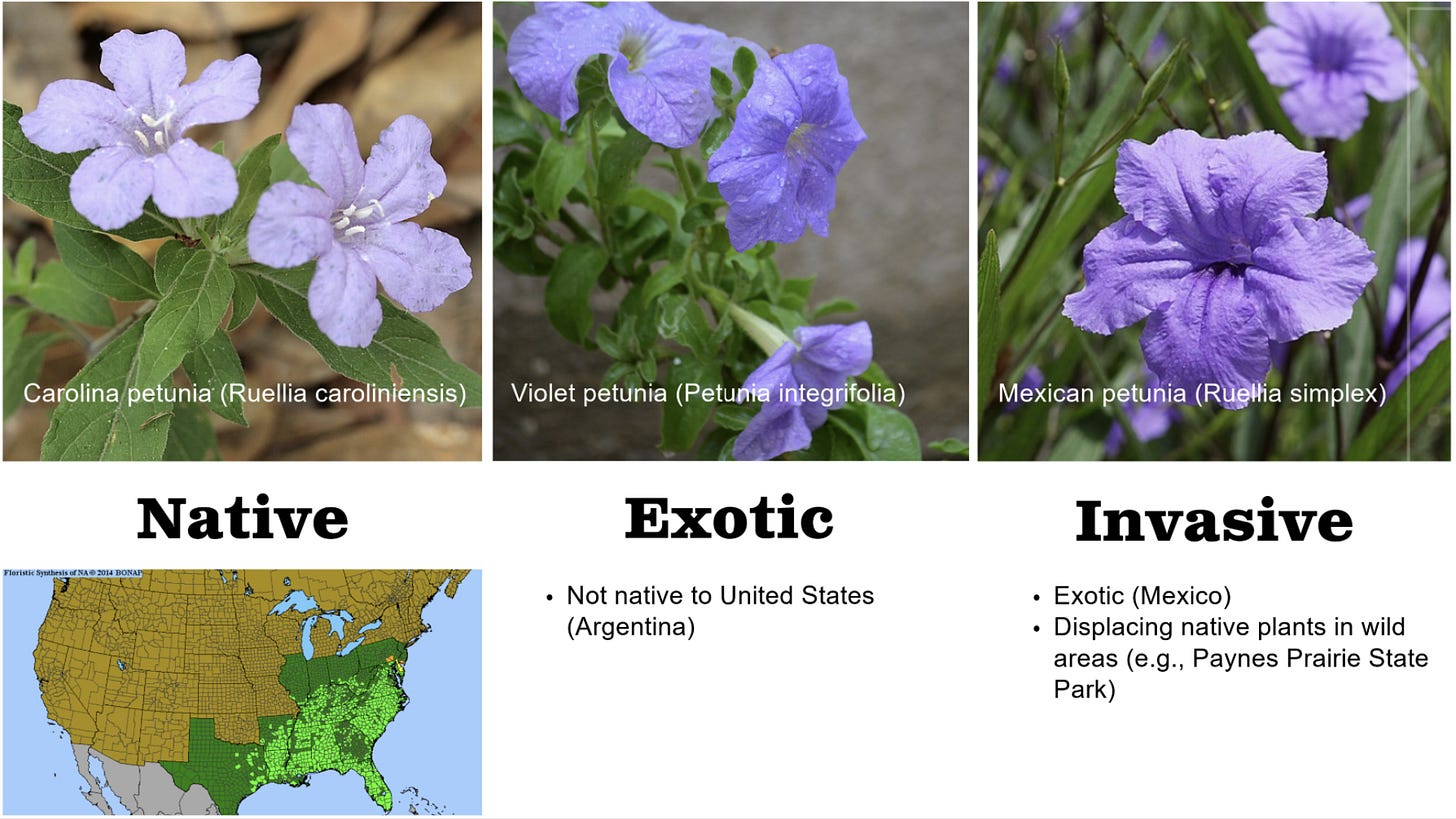

I’d like to clarify what I mean by “native plant,” because I’ve found there’s a lot of confusion. A plant is considered native to an area if it is believed to have evolved there. The Carolina petunia (Ruellia caroliniensis) is considered native to the United States because it was identified here by an early European explorer, Johann Friedrich Gmelin, in 1792. The Biota of North American Program — BONAP — maintains maps, like the one bottom left, that show the native ranges of North American plants by county.

Plants not native to an area are called “exotic” — despite often looking and sounding like natives. For example, the violet petunia, shown in the middle here, is exotic in North America and native to Argentina. It’s the ancestor of most hybrid petunias you find in nurseries. An exotic plant that escapes cultivation and displaces native plants in wild areas is called “invasive.” The Mexican petunia — which I see in yards around Cedar Key — is invasive here in Florida. It has taken over large areas of Paynes Prairie State Park in Gainesville, for example.

A common misconception is that USDA zones indicate native status. They don’t. USDA zones merely indicate the coldest temperatures a plant can tolerate. (See Why I Ignore USDA Hardiness Zones.)

The biggest challenge

Ironically, native plants are hard to find! They are not available at big box stores like Home Depot, where most Americans buy their plants, nor are they generally available at traditional local nurseries. To find a variety of native plants for purchase, you have to go to a specialty native plant nursery. Throughout the country, shopping at a native plant nursery often requires a day trip to a place an hour or two away. (In Cedar Key, we have to drive an hour to buy groceries, so that’s no big deal.)

Of course, you can always propagate plants yourself. You can find information on the internet about how to propagate almost anything. If you collect seeds and cuttings, please do so responsibly, getting permission from the owner or manager of the property where you find them. In addition to buying or propagating native plants, you can grow natives in your yard by learning to love plants that volunteer there. You probably consider them weeds. (You can use the Picture This app to identify a plant; scroll to the bottom of plant pages to see native range maps.)

Wow!

I wrote last time about how Zoe helped me transform my yard in two weeks. I wanted a densely planted, wild yard. But don’t assume native plant landscapes have to be wild looking. You can create any style of landscape with our beautiful native plants. (Design Shortcut for a Backyard Makeover: Yardenalities™ 2.0.)

Massing

The easiest and most ecologically impactful way to introduce natives is to mass them under trees. This creates attractive pupation stations for moths and butterflies.

Pattern

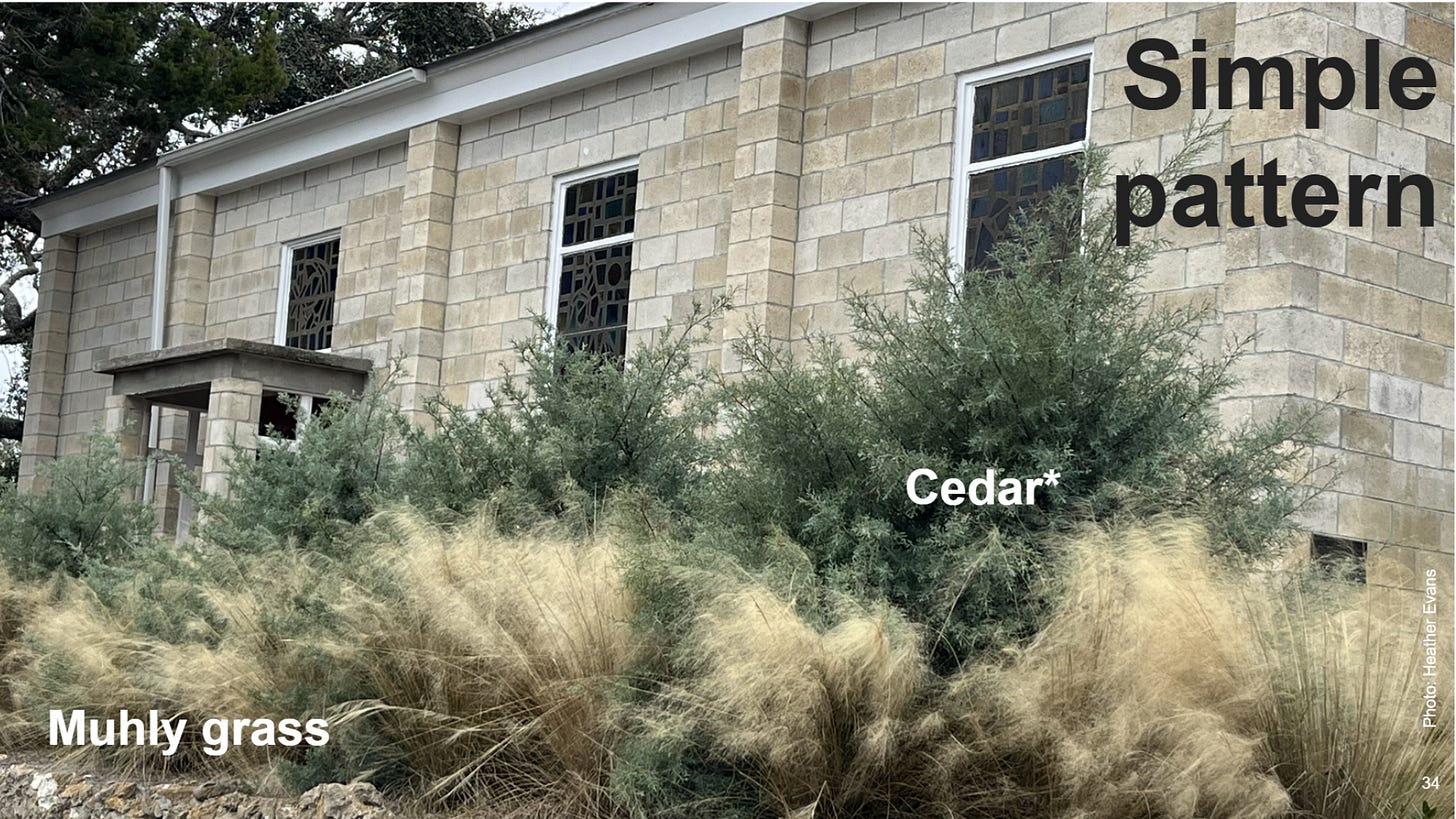

Another attractive, more formal approach is to create a simple pattern of just two species. (The conifer isn’t native eastern red cedar, but it should be:)

Traditional beds

More ambitious gardeners can create traditional mixed beds with native plants.

Shrub dominated

Another approach relies on a narrow palette of characteristic native shrubs. Whichever design approach you choose, lush plantings generally have a positive ROI — in addition to providing food and habitat for birds. This picture is from a $2.8 million real estate listing, which mentioned as a selling point the “natural native landscaping.” (See How Does Landscaping Affect Your Home's Value?)

Thanks for joining me on this journey! Please tell me about your yard transformation in the comments below — or send me a question at heather@designyourwild.com.

— Heather

P.S. Free subscribers, please upgrade to a paid subscription ($30 per year) to join our upcoming workshops and chats.